“Me & Ace” - The Call

Expect one of these posts every week or so, as I work on “Me & Ace.” What began as personal therapy has grown into a full-fledged memoir, with roughly thirty-five chapters already outlined. It’s doing what I hoped it would do: help me process the loss of a friend. The spark came while listening to Eddie Trunk’s impromptu show after Ace’s death, hearing metal stars weigh in. It made sense for them. But I knew the guy. I knew him longer than most. Not better, just our own thing. And our friendship lasted. We had our own thing that started in the Bronx in 1971. This book will bring you through those 54 years.

We were supposed to meet at a county fair up in Lancaster. It was only an hour from my house, and we hadn’t seen each other since I drove to Sparta, NJ to get his signature on a release for my book “Art of the Stomp Box.” He loved the idea and offered a testimonial for the back cover. Fun fact: the release was his idea, and he told me to protect myself in case something happened to him. “Hey,” he said with a wink, “ you never know.”

After all,

I’m the guy who pointed him toward the audition after he’d sit in with my college cover band in the early 70’s. I recorded his Dynasty demos and picked “2000 Man” for him to cut. We spent long stretches together in the ’80s, partying hard and burning fast. We drifted apart in the ’90s, then found our way back through sobriety in the 2000s, when our friendship was at its best. We wrote songs together, including “Past the Milky Way.” I stayed with him and Rachel while we worked. He recorded lead guitar for my BBQ CD.

And we talked about God.

So why shouldn’t I have a seat at the table? I decided to sit at my own table and tell these stories. And it feels really, really good to do that.

Preface-

October 16, 2025. I was on the phone with Crazy Joe Renda of all people, trying to track down Fred Schminke, who’d once written a radiant review of my Cakeman Chronicles show. I’d been toying with reviving it, or at least turning it into prose. Funny who calls who at moments like that.

Joe (Uh, My Name is Eugene) Renda was the co-owner and manager of North Lake Sound - my first studio engineering gig and where I brought Ace to record tracks to support the Dynasty LP.

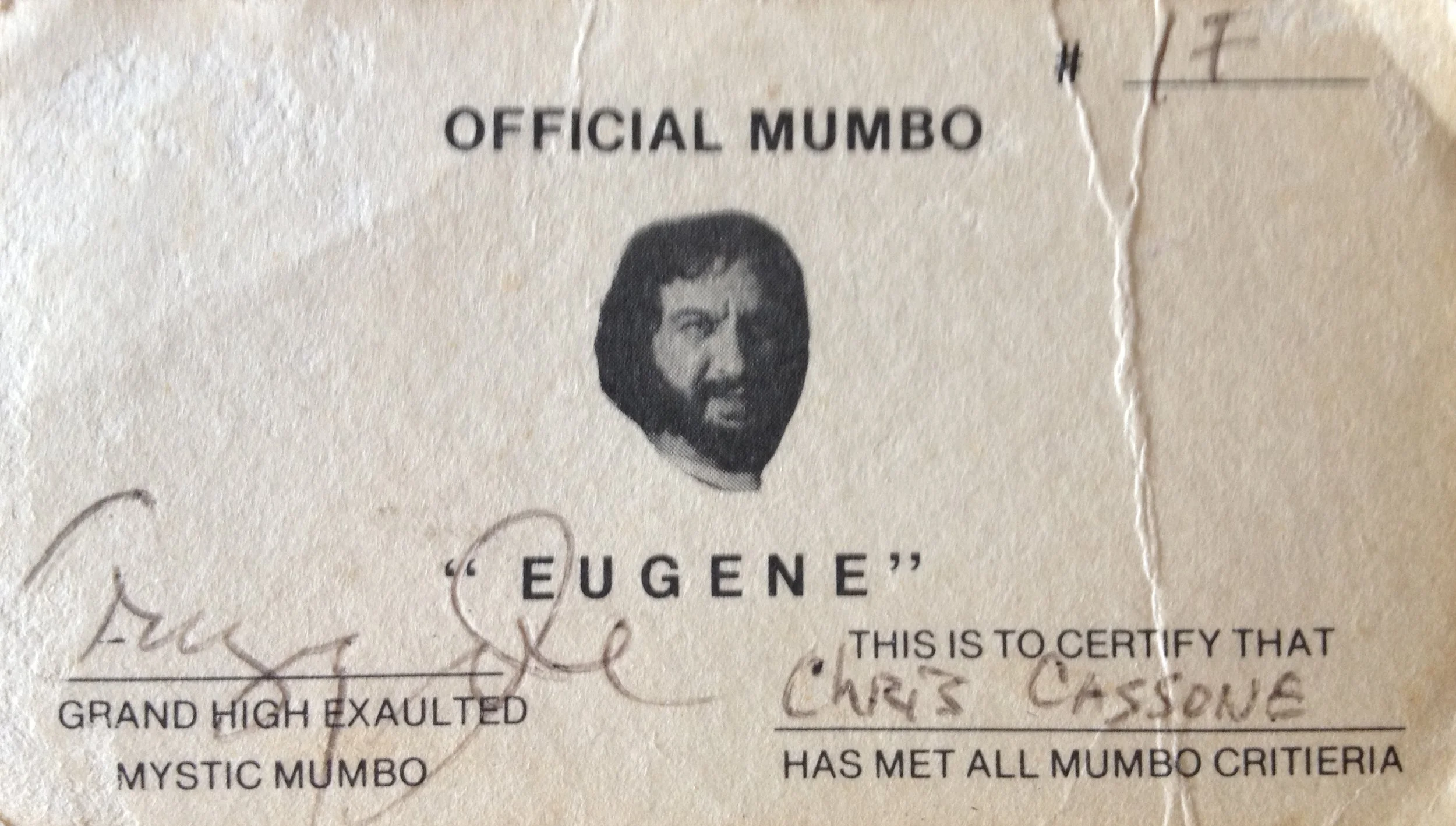

“Hello, Oh Grand High Mystic Mumbo.” That’s how John Regan and I would address him. He started a “club” of all the Variable Speed Band members. Even had cards printed up. If you made him laugh, you got a card. If you were a mega-star, you got a card. (Ace, Frampton, and best friend Billy Vera all got cards.) If you were a fine-looking young lady, you definitely got a card.

A “Mumbo Card” was only issued by Crazy Joe (Ace, Frampton, Bob Mayo, T. Bone Wolk, Vinny Pastore, Buck Dharma, Blotto, among many others.)

“Skinny used to call me that, you know,” he reminisced, referring to John’s nickname after he lost a ton of weight.

So, I’m talking to Joe when he suddenly blurts out,

“Ace Frehley is dead.”

I corrected him immediately. “He is not dead, Joe. He fell. He’s taking time off,” not knowing about the second fall.

“No,” he said, and I could hear him fumbling with his phone. “It says he died in a hospital in Morristown.”

Time slowed.

My laptop was right there. I typed Ace Frehley into Wikipedia.

And there it was. Past tense.

“Ace Frehley was an American guitarist…”

They had changed it already. That fast. I remember thinking: Who are these people?

The numbness came on quietly.

We were supposed to meet at the Antelope Valley County Fair in Lancaster. He was headlining with Quiet Riot and Vixen. His fall and concussion had canceled it. At the time, we thought it was just that — a bad fall on September 25. A concussion. Enough to ground him for a while.

The second fall was different. A full crash down the stairs in his McMansion in Sparta, New Jersey. Big stairs. Hard stairs. He was a big guy — built like a quarterback or tight end. Not the muscle, but the frame. Put long hair and sunglasses on Travis Kelce or Shannon Sharpe and line them up. Same silhouette.

My phone started lighting up. The news cycle went berserk. He was everywhere. Everyone was talking. Nothing made sense.

I needed someone who knew him. Not better. Not more. Just the way I knew him. A friendship that could be put on hold and picked up again years later, like no time had passed.

There was no one to call.

Not Monique. Not close enough.

Not John Ostrowski. He barely picked up when Ace was alive.

Except him. And I couldn’t call him.

So I did the only thing I know how to do. I kept writing. It helped.

What hurt most was knowing a song we started would never be finished. Space Pirates. He loved the idea — a renegade pilot addressing the crowd, recruiting them to maraud across the galaxy. I wanted him to try it in an arena. If the crowd knew it, they would’ve signed up on the spot.

We lived in our own two-hander. A balance. A rhythm.

I tried listening to Eddie Trunk’s show, desperate to hear someone who knew him. But it didn’t help. He spoke as if the rest of us hadn’t really known Ace. Maybe he wasn’t wrong. He had his own grief, I’m sure. Still, it hurt. I turned it off.

When Kennedy died, I was thirteen. I didn’t understand death, but I knew it hurt. I talked to my mother. She understood. We watched the entire assassination drama play out on her TV, sitting on her bed. I had her.

When John Lennon died, it gutted me. I had friends who loved the Beatles. My first wife, Dale, understood the mystery of it. Still, the ache stayed.

This felt different.

This time, I was alone with it.

I am deep into the memoir now and will edit parts and share them with you. Please respond. That would be helpful.

Next post: How We Met